Reflections from the Darkness-sensitive Urban Lighting Course

by Ella Kantola, architect and PhD student at the University of Oulu

Since September 2025, the School of Architecture at the University of Oulu has been running a continuing education programme exploring how darkness can be understood, valued, and designed as part of urban lighting. As part of the Art of Darkness project, two parallel courses — Darkness-sensitive Urban Lighting and Context-specific Light Art — bring together professionals and researchers from diverse fields to rethink the role of light and darkness in contemporary cities.

As a participant and PhD researcher within the project, I have experienced the programme as an ongoing dialogue between theory, practice, and personal perception — one that is still unfolding and reshaping how I approach both lighting design and research.

The two courses run in parallel and share several teaching sessions, while maintaining distinct focuses. Participants form a diverse group of adult learners from across Finland, with backgrounds in architecture, engineering, visual arts, education, urban planning, and communication. Some attend one course, others both.

I participated in the Darkness-sensitive Urban Lighting course, which introduces the role of darkness in contemporary urban lighting design, while working closely with participants from the Context-specific Light Art course, who are developing temporary light artworks for a real urban site. This overlap has created a learning environment in which theoretical perspectives and practical experimentation continuously inform each other.

For me, the course has been particularly relevant. As a PhD student within the Art of Darkness project, focusing on darkness-sensitive lighting in cultural heritage contexts, I came with a background in architecture and cultural heritage, but limited hands-on experience in lighting design. The course has helped me better understand lighting design processes and connect them directly to questions emerging in my doctoral research.

Adjusting to darkness

The course structure combines lectures, workshops, site visits, group work, and independent assignments. Learning began even before the first contact day through two pre-assignments. The first was a dark-time walk, during which participants documented examples of “good” and “bad” darkness in urban environments through photographs and short written analyses. The second was a personal introduction using images, short texts, and keywords to reflect one’s relationship to light and darkness.

These assignments encouraged careful observation of nighttime environments: why some places feel safe, meaningful, or atmospheric, while others feel uncomfortable or problematic. For me, this immediately changed how I perceive darkness. I became more attentive not only to where light was present, but also to where it was absent—and to what that absence communicates.

Sharing these observations revealed how perceptions of darkness differ depending on professional background and experience. Presented on the first day, the introductions helped establish a learning environment where technical, artistic, and experiential knowledge were treated as equally valuable.

Workshops, lectures, and place-based learning

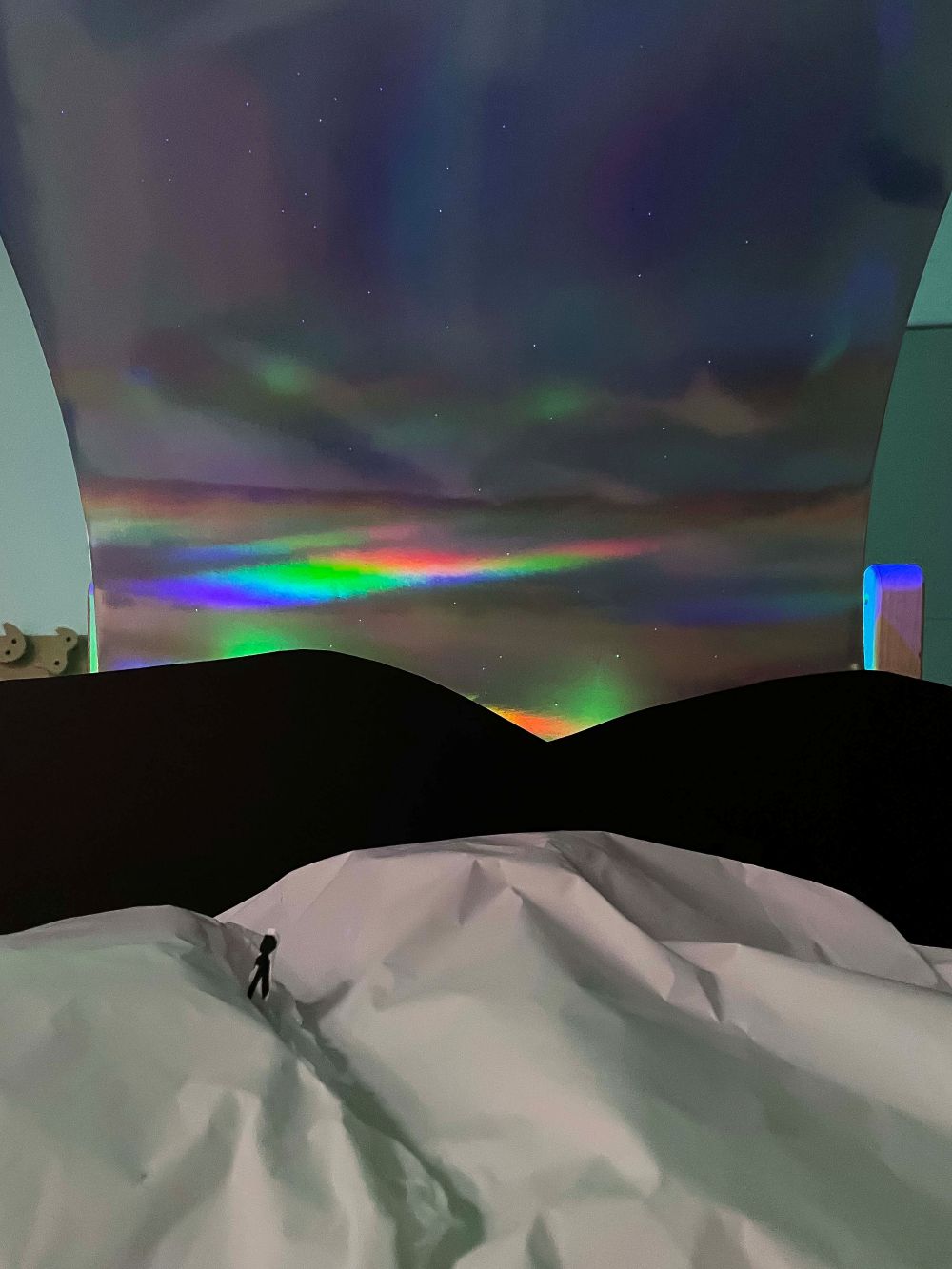

The first joint teaching session brought together participants from both courses for introductions, lectures on urban lighting, a hands-on workshop, and a site visit to the location where the light artworks will later be realised. The workshop focused on personal memories related to light and darkness. Participants translated a chosen memory into a temporary light installation using simple materials and portable light sources.

The exercise demonstrated how lighting can convey atmosphere and narrative, and how abstract memories can be expressed spatially and materially. It also made clear how strongly light is tied to emotion and place.

Subsequent sessions alternated between shared and course-specific content. While the Context-specific Light Art course focuses on artistic production, Darkness-sensitive Urban Lighting emphasises analytical tools, planning-scale thinking, and design processes. These include scenario-based mapping, a “scenario game”, and lectures on European lighting masterplans, coastal lighting principles in Helsinki, and participatory geospatial data in lighting and darkness design. Together, these sessions underline that darkness-sensitive lighting is not only about light levels or luminaires, but also about governance, values, ecology, and context.

Collaborative design and shared expertise

Group work is a central component of the Darkness-sensitive Urban Lighting course. Students work in multidisciplinary teams to develop lighting design concepts for an urban area of their choosing, analysing site conditions, patterns of use, and spatial hierarchies before proposing lighting strategies that balance safety, atmosphere, ecological concerns, and social needs such as accessibility and inclusivity.

Our group selected a multifunctional park close to the city centre, combining recreational routes, sports facilities, and a small harbour area. As an architect, I contributed to spatial analysis, mapping uses and the broader urban context, and producing visualisations and sectional drawings. Other group members brought complementary expertise, grounding ideas in technical feasibility, strengthening communication, and sharpening the narrative of the final presentation.

This multidisciplinary collaboration has been one of the course’s strongest assets, highlighting how darkness-sensitive lighting design benefits from integrating multiple perspectives.

Beyond group work, online seminars allowed participants to present topics related to their own professional interests, ranging from park lighting and natural-area illumination to cultural heritage lighting, communal light artworks, urban planning processes, and DarkSky principles. Visiting lecturers complemented these sessions, reinforcing peer-to-peer learning and demonstrating the broad applicability of darkness-aware thinking.

Learning beyond the classroom

What stood out to me throughout the course was how learning extends well beyond traditional classroom settings. Lectures and readings are complemented by site visits, dark-time walks, workshops, programming demonstrations, and hands-on testing of lights both indoors and outdoors. Practice-based learning deepens theoretical understanding by showing how abstract principles translate into real environments.

This emphasis on experimentation is especially visible in the Context-specific Light Art course, which focuses on creating temporary light artworks along the shoreline in Pikisaari. Through programming workshops, outdoor testing, and iterative design, students explore how conceptual ideas can be translated into programmed light and spatial experience. The artworks — currently in development — address themes of disappearance, change, and vulnerability, making overlooked layers of the site visible through light.

The most recent live session of the Darkness-sensitive Urban Lighting course brought these strands together through group presentations and discussion on public attitudes towards darkness in Nordic contexts.

The diversity of design approaches demonstrated that lighting design does not rely on increased brightness to achieve safety or orientation. Thoughtful use of light — and deliberate use of darkness — can support movement, ecological values, and atmospheric quality. Brighter is not always better; in fact, I have come to see that it rarely is.

This last session concluded with a dark-time walk through Oulu city centre. It gave us an opportunity to observe familiar and unfamiliar places with new sensitivity to darkness, noticing not only lighting solutions but the absence of light, and the transitions between them — seeing darkness in a “new light”.

Reflections and what I take forward

Although the main live teaching sessions are now completed, learning continues through reflective learning diaries, the ongoing development of the light art exhibition, upcoming seminars and webinars, and participation in the LUCI Cities & Lighting Summit in Oulu, at the end of February 2026.

The course has shown that darkness-sensitive urban lighting is not a fixed method, but a mindset. It requires sensitivity to context, openness to collaboration, and recognition of darkness as a spatial, ecological, and cultural value.

From a student’s perspective, it has provided both practical tools for lighting design and a shared language for discussing darkness as a meaningful component of urban environments — and a reminder that designing with light also means knowing when, where, and how to leave space for darkness.

Photos: © Janne-Pekka Manninen, Ella Kantola and Riikka Vuorenmaa